Kept Keeping My Eyes on the Divine Drip Drop

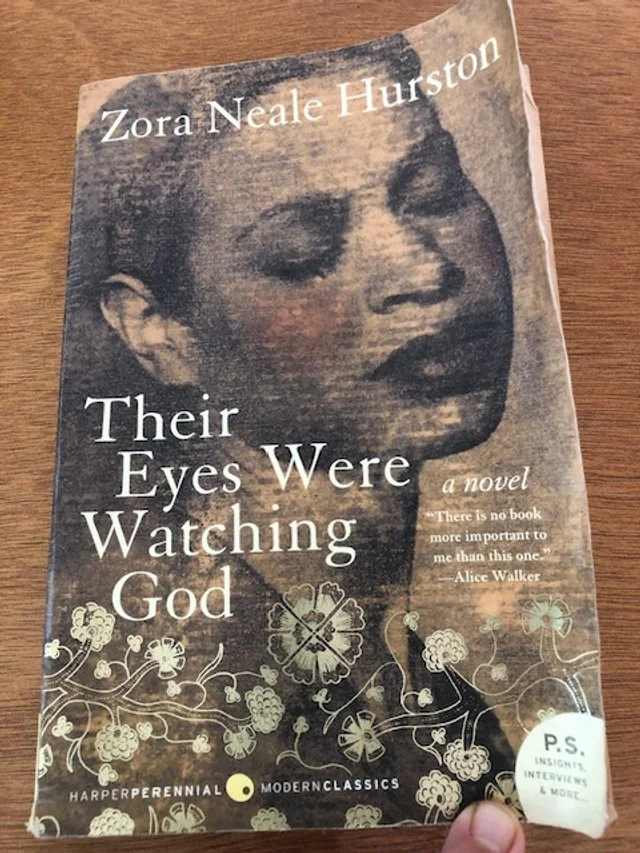

In an electrical novel Their Eyes Were Watching God the fiction prose is highly charged with humanity's current as the story unfolds. Author Zora Neale Hurston went to her grave a virtual unknown until a feminist press made her discovery. Gifted readers we all became. Some writers decode this brief life on levels often rendered invisible given mundane responsibility that requires our full attention anyway.

We show up for each other. Yet literature like Hurston's takes the ordinary to complex empathy that flat out glues your imagination to the page, held quiet and still by a surprising electrical jolt, subtle lightning that strikes awareness and from which we return better ready for the day forward.

Anyone who ponders behaviors that seem contrary to your life's progress often asks in curiosity if nature or nurture accounts for why we say one thing and do another. Characters in novels demonstrate all that messiness at a cozy refrain. Once we put the reading down, a return to familiar messy continues. I guess that is why I find fictional characters intriguing. They lend my life examples on how to act differently during the day, running on more aware ampage. In this way, literature serves us well.

One scene from the novel portrays how to decide whether to stay or flee when extreme inclement weather is to arrive. Several days before the tempestuous hurricane strikes the Glades, dozens of Native American clans walk single file to higher ground. They intuit and they trust knowing nature's signals without being told by people because listening to wind, rain, sand, leaves, trees, insects, animals, and infinite more inside an ecosystem takes willingness to train in this type of “listening.” Native American historical culture has nurtured innate nature—the physical biology each of us is awarded from the start—to seek safety as sixth sense intuition (nurture) and physiology (nature) impels. This is the nurture and nature of humans to trust nature, a reciprocity always available if able to listen.

In Lee Irwin's book The Dream Seekers, Native American Visionary Traditions of the Great Plains he describes how a few in the culture were called by thunder spirits to “the potency of thunder power so great that its manifestation reversed the normal order of social relations...this quality of the visionary topology corresponds to the dynamics of the natural environment that contained the unpredictable, the terrifying or the overwhelming power of natural events” (54). Given the status of listening to thunder's message, the Native American held his or her tribe's persuasive power—and in the novel's hurricane scene nature's message is to leave early.

Leaving well before the hurricane strikes is spiritual knowledge few others are portrayed as having in Hurston's novel. Even so, some creatures who dwell this earth also flee: raccoons, snakes, dogs, cows, rabbits, mice, and horses. Scurrying in survival instinct these animals make for a successful escape. Perhaps we cannot fathom why some humans can sense danger on an intuitive physical level yet stay anyway. Could be a sort of willful not listening.

The scene's setting is the deep American south where human complexity along racial lines spirals into grace and yet mayhem even when a hurricane is not about to disperse the waters of a lake 40 miles wide and 60 miles long. Given slavery's imprint on American lives, the white land owners decide to stay for who in the name of God would uproot what is assumed such a privilege as owning sturdy homes and profitable farms? African Americans living on these farms, in their own dwellings, decide in varying ways to protect life and limb. Many leave immediately.

Others watch their white bosses not worry and conclude that the hurricane is overrated and continue living as if. Three or four days before the storm arrives, some signs of disrupt are there as in increased winds and scattered rains, yet still time to gather friends around for shared meals and evening music jam sessions. The central character Janie and her husband Tea Cake decide to stay in their home despite friends knocking at their door, having a car ready to drive away and thus deploring them to leave. They stay.

In extreme emergency we blend that feral instinct, our natures, to survive no matter what and throw caution to the wind. Notice how so. “As soon as Tea Cake went out pushing wind in front of him, he saw that the wind and water had given life to lots of things that folks think of as dead and given death to so much that had been living things. Water everywhere. Stray fish swimming in the yard. Three inches more and the water would be in the house. Already in some” (160). If caution is nature that has been nurtured, learning from life's vagaries, then how to blend the two when havoc arrives?

The decision making happens in instant increments, sometimes forward and sometimes backward, bringing all that we have known into the immediate what we need to know for rapid doing in the moment. The struggle is real in Hurston's literature scene. “The wind came back with triple fury, and put out the light for the last time. They [Janie and Tea Cake] sat in company with the others in other shanties, their eyes straining against crude walls and their souls asking if He meant to measure their puny might against His. They seemed to be staring at the dark, but their eyes were watching God” (160). Soon, Janie and Tea Cake are swimming in avalanche waters fighting for their lives. And I will not reveal what occurs plot wise because I wish for you to read the novel. Today. Witnessing literary scenes on the page changes us on the inside.

Earlier in the novel Janie has married a dominating business entrepreneur who refuses for her to ever let her hair down, literally, since she wears a hair wrap for all 20 years they stay a couple. Her husband fears her female appearance, that rageful jealousy commonly seen in hetero couples. Not a dismissive on straight people simply that soulful nurture side of life soars way beyond how a woman looks. Janie's second husband Tea Cake saw this—her advanced spirit for living life free—in her from their first encounter. Janie threw caution to the wind and married a partner who had little to no money while she had significant riches for that historical time period yet Tea Cake never asked for one penny. He saw Janie's spirited confidence and knew to cultivate that through spontaneous, thoughtful love.

The lousy husband owns a store, and as in many rural small towns, folks gather on the wide porch to swing a rocking chair and an intriguing question. One of the five men who gather to play checkers, buy Coco Cola bottles from the store's ice box inside, and compete on language dance moves poses an inquiry: “Whut is it dat keeps uh man from gettin' burnt on uh red-hot stove—caution or nature?” (64).

The debate goes viral right their in the country air as all five yammer away to elucidate their points. Playfully and critically they admit through one dialogue line after the next that the answer is simply unknown. One character does conclude a stance though. “If it was nature, nobody wouldn't have tuh look out for babies touchin' stoves, would they? 'Cause dey just naturally wouldn't touch it. But dey sho will. So it's caution” (64).

In this conversation's flow are some queer tangentry for as the men elevate Big John de Conqueror as an example of royal nature originating in Egyptian time epochs, one concludes that Big John had salt flavoring. And postures that “Me mahself, Ah got salt in me. If Ah like man flesh, Ah could eat some man every day, some of 'em is trashy they'd let me eat 'em” (67). Strayed the conversation has and, then again, perhaps not.

That Hurston places this dialogue directly after the caution or nature question shows one response—that in an all male culture admiration for male hubris is valuable. And that play-acting (or what we call gender as performance in queer culture) applies when females show up. For a minute later “here come Bootsie, and Teadi and Big 'oman down the street making out they pretty by the way they walk. They have got that fresh, new taste about them like young mustard greens in the spring, and the young men on the porch are just bound to tell them about it and buy them some treats...they know it's not courtship. It's acting-out courtship and everybody is in the play. The three girls hold the center of the stage... (67). Performance culture is all on the queer stage and for a novel published in 1937, Hurston's prose was way ahead of her time.

When I read the novel a few days ago, I was gifted these ruminations on how these fictional characters forge lives in an inextricable weave of nature and nature—through nature's severe weather, coupling relationships, and ordinary supportive friendship. As literature motivates me I reflected on my own complexity that I was born with a biology prone to addiction. So what remains valuable and vital is that I cultivate or nurture an environment that encourages healthy living for my own life and all those who I love.

At a table of seven women this morning, situated on church grounds in the Hawaiian countryside, I belonged and took a chair myself. We read sobriety literature, and conversed, and laughed, and we kept supporting that divine drip called serendipity that needs support so as to never drop. And once those who love us witness the attempt to stay in healthy sobriety so that “in this area there are seldom any questions of timing or caution” (83) as one recovery book describes. Then the right time to seek spiritual action is in the very now of the moment, however blending nature and nurture propel you forward.