Graveyard Birthdays

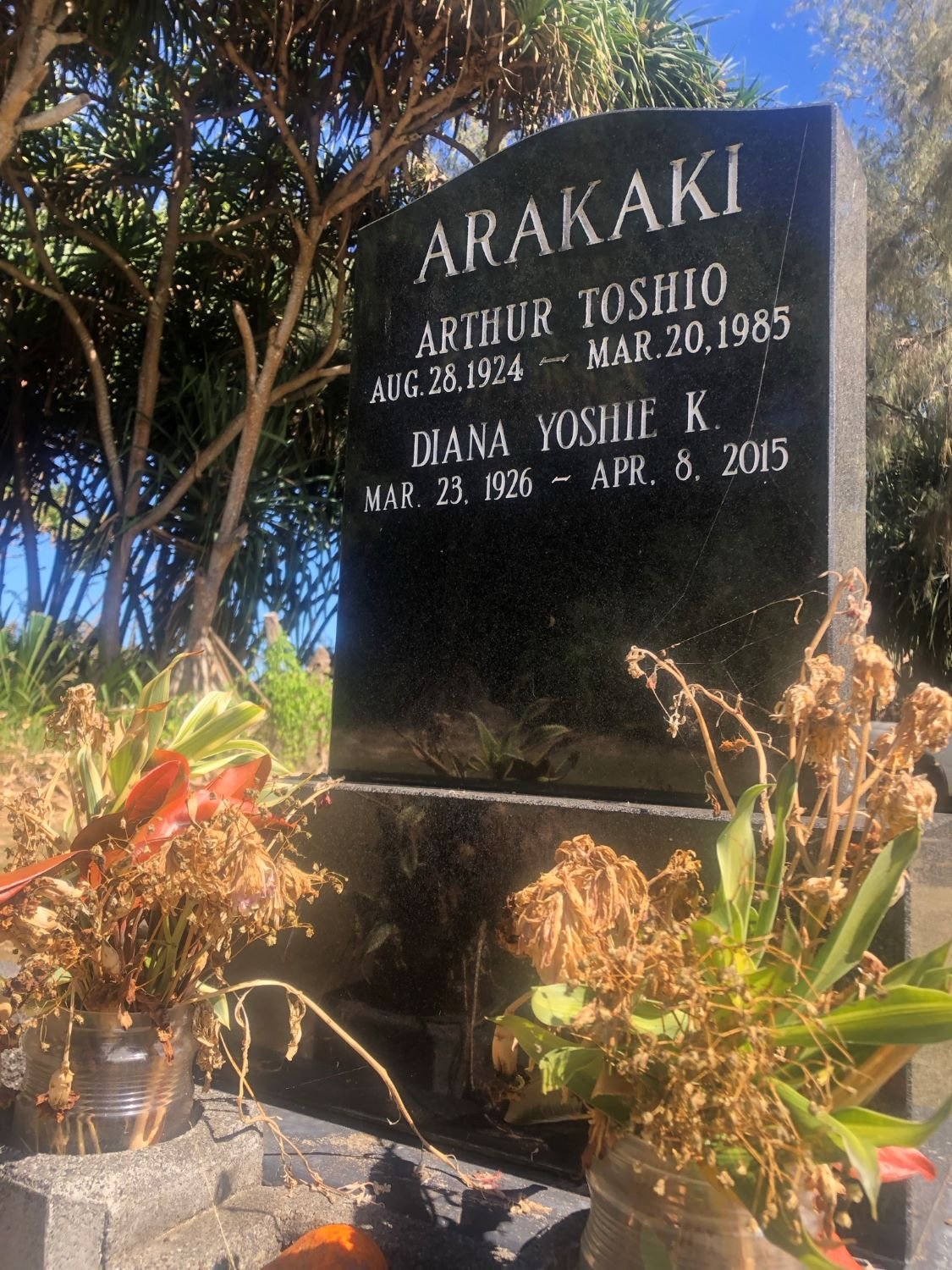

On my birthday, I sometimes stroll through graveyards to celebrate. In Kohala’s countryside the cemetery plots tell stories on tombstones. Peculiar timelines, diverse names, and life roles are etched into cement or marble. Relying on fiction to respect and imitate reality, one sample name reads Pedro Alfonso, son, born September 17, 1982, and died May 22, 1988. He was six years and ten months old when we lost him. Another plot exhibits the bare minimum place marker with a one-foot picture frame, a printed piece of paper inside, stating the person’s basic info, which the adjacent church has stabbed in the grass. I suppose the family got busy.

Most days in my life now bring that joyful nerd sensibility, so I am not pacing dead earth (aina), or rather aina where the dead reside, as a morbidity project. I am happy to visit graveyards. They have become an aspect of local Hawaiian geography that I treasure. Maybe that is the point. How we celebrate death, like we party on birthdays, repurposes the living days ahead.

For example, Americans have a national tombstone. When you get a chance, watch the documentary on Maya Lin, a 21-year-old Yale college student who, on a whim, submitted an architectural concept for the Vietnam War Memorial. (Documentary is titled Maya Lin: A Strong Clear Vision.) Of the many entries, hers was selected because she envisioned naming thousands of dead soldiers, etching who they were into shiny black granite. One long line stretches on the flat bottom, under the gradual triangle sides, a monument ascending from earth’s soil. In a way, her project-drawing depicted a majestic, shared tombstone, telling the specific Vietnam War story—all those American lives sacrificed.

Maybe I explore my own birth when I view death from diverse angles. On February 2, 2022, I am turning 57 years old. How random that I aged this far. So many life variables stacked up to predict a different toppling. Yet in this sturdy health—my female body, sobriety in emotions, and spiritual gifts—that I enjoy now, I can easily look back and see how lucky each day is, so the graveyard adventures cheer me up to honor those who have left the corporeal experience for the long-term spiritual one.

Walking graveyards feels like opening pages to a history book. If we neglect constructive memories from the past, how can we live in the present more honestly? For instance, another Vietnam War seems unlikely. Perhaps America learned. Or my perception that drinking alcohol is a death sentence given my genetic DNA and the ohana tombstones already in tribute. Several of my family are gone. Likewise, on my birthday this year, I give myself the gift to not smoke cigarettes. We have lost a few. Reflecting on history, then, seems pivotal to live fully in the present, designing a consequential future.

Some cultures even throw parties as in El Dia de Los Muertos to honor the dead and evaluate their lasting influence. In the movie Coco, the main character is 12-year-old Miguel and he traverses this side and the other side reconciling his ambition to become a musician as was his great-great-grandfather. But the skeleton Hector must lead the way. In the movie audience, we learn to search our ancestry so instructional ghosts continue to teach in our lives. One question family ask is how do those gone still influence our lives?

Considering my humble inner-world (go ahead, call the contradiction: am I “humble” if stating so?) that surprisingly breaks into Spanglish, declaring that mi vida tiene buena suerte—my life has such luck—some blessings are in tutorial ghosts. If I reflect back on my father’s death, 72, on June 11, 2011 and my older brother’s death, 56, on March 6, 2019 and my aunt’s death (my mom’s twin sister), 80, on March 12, 2016 and a best friend’s death, 63, on January 1, 2014 and other dire losses in my life so far, I realize this classroom, a sort of Death Studies 101, has been teaching me all along.

The lesson is to live each day as if the last one gifted to you. And I strive for that in two strategies: a thorough joy in simplicity (cinnamon gum bursts me into a wide smile) and that I treat others well. For many years, I was challenged to activate either. And now I seem more capable. Buena suerte.

And then I realize that perhaps equally active to their influence on me, is the impact I have on them, the liminal ghosts, wherever los muertos are, through how I live my life. So many people in my life I admire, yet on my most genuine life strand, this lesbian sensibility, at times an absence exists of role models. So, during more than a few days, I reinvent to align with how I feel inside. And as I do, others witness my behavior as perhaps innovative, something new, something queer—in other words—and take heart. Especially the folks in my life who have died along the way. Maybe I flatter myself, but I truly believe that loved ones already on the other side, are happy when viewing my life choices.

When my son was born October 21, 2010, a fantastic new friend arrived in our family. She had that joyful belly laugh and dancing eyes to match; we kept saying thank you over and over for all her kindness. Her spirit appreciated kid time as the most enriching. She adored Darien; she and I also had AA in common. The third year our friendship continued, she became sick and I never guessed how gravely. That look she gave me is one I can still see.

Departing from an impromptu birthday party for Darien, his third, walking through her kitchen to the apartment front door on October 21, 2013, I turned around. She stared at me with these translucent eyes, beckoning me to say more, and I attempted to decode what she needed. Effusive in my thank youze for the shared birthday party, I stumbled to the car. I gripped the steering wheel tight for more than a while. A few prayers, a couple exhaled breathes, and we drove away. That was the last time I saw her, for she died January 1, 2014.

One everlasting method to endure and then transcend grief can be reading books, especially out loud. Helpful truth that the process has varying degrees of bookshelf life as in the dead one’s positive impressions last for good and the negatives to let go, we call “self-work.” Darien was three when Aunty Pat died, so as serendipity goes for an active reading family like ours, we had the book Hinepau on the shelf. The Maori legend from New Zealand narrates how Hinepau, an eccentric woman with emerald-green eyes who weaves strange patterns upside down, returns to help save her village, the same clan who shunned her for being so odd.

After dying, she is said to continue smiling at her people from the brilliant orange infused clouds in the crisp blue sky at sunset and sunrise. In those first days after she died, Darien and I were waving at Aunty Pat smiling in the clouds, through to us. I asked Darien to conjure her as a sort of Hinepau. For a three-year-old he “got” this and even this morning while driving in the car, we stared up to abundant cotton-candy pinkish orange sunrise clouds, saying hello to Aunty Pat. Darien is now 11, yet the simultaneous healing and grieving method seems to work.

And to process my older brother’s death from stomach cancer at 56, my son and I read Harry Potter. Gratefully, my brother’s wife and two daughters—one in high school and the other in college—continue thriving in their lives. Especially the first year after the loss, our family found reading aloud soothing. Characters that we cared about so much kept dying left and right in the novel. The painful stab to witness together, my son and I, another loss in the ongoing fictional saga, kept priming us to heal in “real” life. One of life’s mysteries on how many of the tears that fell during these reading sessions were for the Harry Potter characters or my older brother. Besides the point, I guess.

Took one year before cancer ended my older brother’s life, and the year and a half after, yet we read aloud every word in all seven Harry Potter books, totaling more than a few thousand pages. The power of fiction to role play, even in casual conversation, making empathic choices in tumultuous times feels like, for our family, steadfast healing through imagination.

Another way to share reciprocal inspiration, as in the dead continue motivating while the living demonstrate purposeful lives, is the Hawaiian aumakua. The concept exemplifies how a nonhuman such as an animal or insect has spiritual energy, a type that fits your own. For a few decades the turtle, or honu in Hawaiian, has been mine. Ever slow, ever steady, in my shell making progress, and against the rabbit, winning the race. The last year or so the butterfly seems more apt given inner-changes that bring smoother life ease, the connotation of being in flight.

And as the dead and the alive communicate in diverse ways, my son and I often discover aumakua spirits in animals who now, probably, represent the deadly departed. They return in this form to say hello. Since every day, and mostly all day, we are suffused in Hawai’i’s nature, some spiritual ping will emanate from a nearby animal—bird, moth, dog, centipede, cockroach, wild pig, horse, cow, duck, chicken, gecko and many more. Darien and I will chuckle, concluding, “Oh, that’s just so-and-so saying hi.” We stand still, reciprocating glad aloha, and then wave goodbye.

And graveyard tombstones resemble books in a way, all that messy detail to decode. Reading seems solitary but the author imprints so much message while the reader conjures her own. Takes two. Similar work to send a message and to create one as the receiver, which happens while standing above a graveyard. Folks leave the most bizarre (read: valuable) items: stuffed animals, plastic flowers, Jack Daniels bottle, life size glossy photo, Coco Cola bottles, dice, miniature white picket fence, fuzzy carpeting, all kinds of kids’ toys, kukui nut leis, Astro turf plastic lawn, beer bottles, shoes, flags, and other symbolic tchotchke that have eternal meaning to those alive and those dead. On my birthday, I enjoy making guesses as to the meanings.